The University of the Philippines College of Music is pleased to announce its major events this month, promoting critical thinking on Filipino music that spans the categories of indigenous folk, popular, and art. All events are free and open to the public. Please encourage your students to watch and listen. Also, please forward these to your friends and egroups.

1.) World premiere of the latest contemporary Filipino opera, Diwata ng Bayan, at CCP on 9 February, 8pm. Libretto by Ed Maranan and Music by Carmela Sinco. Dr. Ramon Acoymo, stage and co-music director.

image1.jpeg

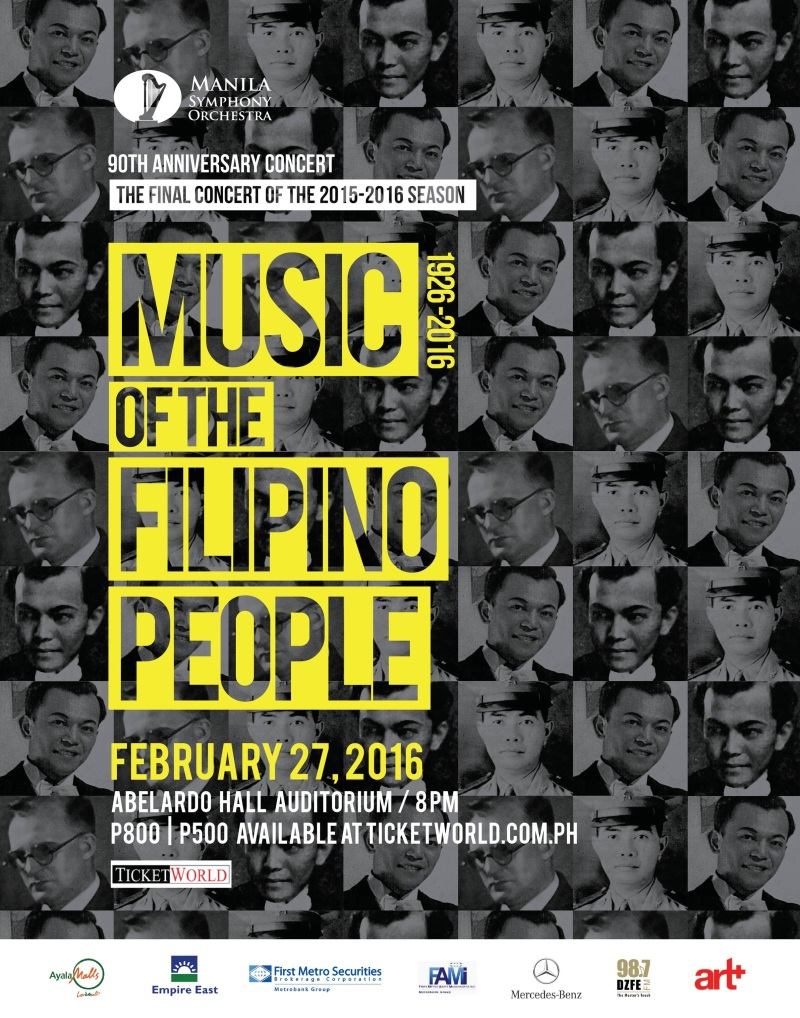

A latest addition to the Philippine art music literature, Diwata ng Bayan will have its world premiere at the Tanghalan Nicanor Abelardo (Main Theater) of the Cultural Center of the Philippines on February 9, 2017 at 8:00 PM. It is free and open to the public. The music is composed by Carmela Sinco, granddaughter of former UP President Vicente G. Sinco, with the libretto by Ed Maranan, Prof. Dr. Ramon Acoymo as stage and co-music director, the incumbent chair of the UP College of Music Department of Voice, Music Theater, and Dance and Assoc Prof Rodbey Ambat, conductor. The opera is set at the end of the 19th century, during the transition from Spanish to American colonial rule, depicting the romantic story of Matias Ylagan and Mayumi Lualhati whose passion for each other goes hand in hand with their patriotism for Inang Bayan. The work draws inspiration from the story of Andres Bonifacio and Gregoria de Jesus of the Katipunan, and the “seditious” dramas of Aurelio V. Tolentino, whose 150th anniversary is being celebrated this year.

Free tickets are available upon request. Please contact Berns or Lolit at 0919-567-0465 or 981-8500 Local 2639.

2.) Symposium on Transcultural Philippine Music (third of a series)

A half-day symposium on Friday, 17th of February, 1-4pm on the roots of transcultural Philippine literature and music, particularly focused on popular Filipino culture as emergent to Philippine alternative modernities. Papers by distinguished Filipino intellectuals Dr. Epifanio San Juan Jr, UP Prof Emeritus Steve Villaruz, Dr. Elizabeth Enriquez, and Dr. Maria Rhodora Ancheta will tackle issues pertinent to vernacular literature, to the folk dance canon built by Francesca Reyes Aquino, radio songs, and on Katy de la Cruz’s bodabil songs, respectively. Papers by Prof Villaruz, Drs. Enriquez and Ancheta will be annotated with dance and music performance by UP Dance Company, UP Jazz Band (Prof Rayben Maigue), with arranger Krina Cayabyab.

image1.jpeg

image1.jpeg

Below is the broader theoretical context of the symposium, which disseminates the College’s EIDR grant from the office of the UP vice-president for academic affairs.

The issue of class (status group) is a vexing problem in the theory of modernity in the Philippines. This problem needs to be understood in the context of the particularities of cultural development in the country within the history of entanglement with the cultures of two empires–Spanish and American. As a response, Filipino intelligentsia from various social class positions articulated local modern visions that were alternative to the empires’ grand, globalizing narratives of development and progress. They made traversals, constructing innovative artistic expression, embodying grassroots Filipino folk-popular sentiment and culture as an alternative response to cultural empirialism and thus built what one would call as “alternative Philippine modernities.”

The articulation of Filipino modernities in the arts had two tendencies: 1) the middle-class elevation of the folk materials to “high culture” (e.g., use of balitao and kundiman in Western classical-art forms), and 2) the channelization of the Filipino folk-popular to wider audiences via the mass media, which was not isolated from the first tendency.

In this symposium, we look into these two tendencies, but give more space to the realm of the second in which vernacular Filipino literature, folk dances, Filipinized bodabil, and radio songs got broadcast audiences attuned to the emerging “alternative Filipino modernities.” This strand emerged during the formative years when capitalism and flow of images and ideas accelerated between 1898 and 1941.

It was certain that the second and third generations of Filipino intellectuals–“sandwiched” between global empires and local worlds–drew inspiration from local Filipino cultures, thus creating national hegemony beyond their class origins. But the details into how the creation of that national culture and patrimony will be in the specific topics to be elaborated in this symposium.

3.) Documentary on traditional Philippine music

image1.jpeg

Lastly, the College respects the cultural difference and appreciates the resilience of the music of the marginalized groups in Philippines with a video documentary produced and directed by Dr. Jose S Buenconsejo, as part of his grant from the National Research Council of the Philippines. Dubbed “Sound Tenderness: Music of the Non-violent Palawanun Society in Southern Philippines,” this will be previewed on Thursday, 23 February 2017 6:00 PM. Abelardo Hall Auditorium

Below is the gist of the documentary:

Non-violent society is extremely rare in the human species. The Palawanun in Southern Philippines is an exceptional case whose culture is manifest in their delicate and tender music, save the boisterous gong and drum in celebratory dance and, in former days, rice wine drinking feasts.

In Palawanun society, negative emotions like anger are not channeled to violent acts–men and women nor children never hurting each other–but by repression, a number of times of which has led to tragic suicides.

Palawan people rationalize acts of suicides as “hereditary,” i.e., if parents commit suicide, then children would most likely follow them. This documentary suggests that the predisposition to suicide is not genetic but is underscored by social conformity. Palawan music is a compelling evidence of conformity.

Music, which is often seen as providing a moment of forgetfulness to sour interpersonal relations, is not a solution to suicide. For a society who values working in groups, alienation from society is the most painful human experience. Rather than forgetfulness, music accentuates the feeling for togetherness, the absence of which means death or embracing the opposite of society which is nature.

This documentary, filmed in Minahaw, Bonobono, Bataraza, Palawan in 12-16 August 2016, contemplates on Palawanun music in the praxis of its social use.