Afable, Cynthia. 2017 “The Poetics of Paawitan in a Tagalog Community in the Province of Quezon, Philippines.” PhD ethnomusicology dissertation, Philippine Women’s University.

Africa, Antonio. 2016.“Expressions of Tagalog Imaginary: The Tagalog Sarswela and Kundiman in Early Films in the Philippines (1939-1959),” PhD ethnomusicology dissertation, Philippine Women’s University.

Archiving Filipino American Music in Los Angeles (AFAMILA): A Community Partnership with Kayamanan Ng Lahi. Collection 2003.05. Ethnomusicology Archive, University of California, Los Angeles.

Balance, Christine Bacareza. 2016. Tropical Renditions: Making Musical Scenes in Filipino America.Durham: Duke University Press.

Brennan, Philomena S. 1984. “Music Educational and Ethnomusicological Implications for Curriculum Design Development, Implementation and Evaluation of Philippine Music and Dance Curricula.” PhD dissertation, University of Wollongong.

– – -. 1995. “Philippine Rondalla in Australian Multicultural Music Education.” In Honing the Craft: Improving the Quality of Music Education: Conference Proceedings of the Australian Society for Music Education, 10th National Conference, edited by Helen Lee and Margaret Barrett, 54-57. Hobart, Tasmania: Artemis Publishing.

Buenconsejo, José S.. 2008. “The River of Exchange: Music of Agusan Manobo and Visayan Relations in Caraga, Mindanao, Philippines.” DVD. Video documentary accompanying book Songs and Gifts at the Frontier.

– – – . Editor. 2017. Philippine Modernities Music, Performing Arts, and Language, 1880-1941.Quezon City: The University of the Philippines Press.

Burns, Lucy Mae San Pablo. 2013. Puro Arte: Filipinos on the Stages of Empire.New York: New York University Press.

Capitan, Amiel Kim Quan. 2017. “Dis/Re-Integration of Traditional Vocal Genres: Cultural Tourism and the Ayta Magbukun’s Koro Bangkal Magbikin in Bataan, Philippines. “ Proceedings of the 4th Symposium of the ICTM Study Group on the Performing Arts of Southeast Asia, Penang, 2016, 58-59.

Carranza, Anna Patricia R. 2020. “100 Years in Retrospect: Articulations of Philippine Identity in the Undergraduate Programs of the U.P. College of Music (1916-2016),” Master of Music thesis, University of the Philippines.

Cayabyab, Cristina Maria P. 2015. “Filipinizing Western Musical Theater: An Analysis of Ryan Cayabyab’s El Filibusterismo.” Musika Jornal11:2-37.

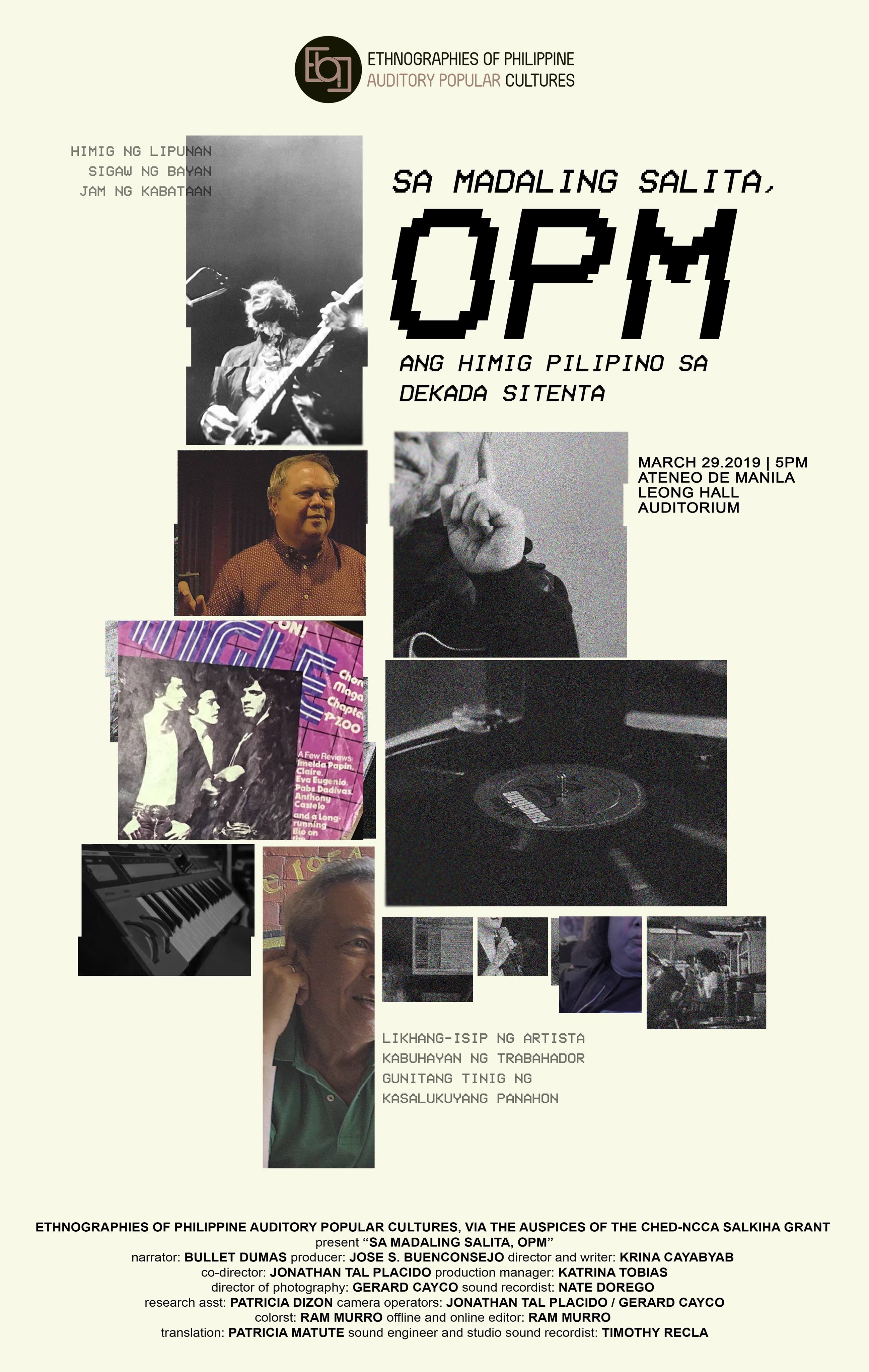

– – -. 2018. “Session musicians and the golden age of Philippine popular music, 1973-1987.” Master of Music thesis, University of the Philippines.

Chua, Maria Alexandra, Iñigo. 2017. “Composing the Filipino Music Transculturation and Hybridity in Nineteenth Century Urban Colonial Manila (1858-1898),” PhD in music dissertation, University of the Philippines.

Costes-Onishi, Pamela. 2010. “Kulintang Stateside: Issues on Authenticity of Transformed Musical Traditions Contextualized Within the Global/Local Traffic.” Humanities Diliman7 (1): 111-139.

Cunningham, Roger D. 2007. “’The Loving Touch’: Walter H. Loving’s Five Decades of Military Music.” Army History 64: 5-25.

Dadap, Michael. 2007. The Virtuoso Bandurria.Dumaguete City, Philippines: Unitown Publishing House.

Devitt, Rachel. 2008. “Lost in Translation: Filipino Diaspora(s), Postcolonial Hip Hop, and the Problems of Keeping it Real for the ‘Contentless’ Black Eyed Peas.” Asian Music39 (1): 108-134.

Ellorin, Bernard B. 2008. “Variants of Kulintangan Performance as a Major Influence of Musical Identity.” Master of Arts thesis, University of Hawaii at Manoa.

– – -. 2015. “Trans-cultural Commodities: The Sama-Bajau Music Industries and Identities of Maritime Southeast Asia.” PhD dissertation, University of Hawaii at Manoa.

Gabrillo, James. 2018. “Rak en Rol: The Influence of Psychedelic Culture in Philippine Music.”Rock Music Studies, special issue on Global Psychedelia and Counterculture, edited by Kevin Moist, 5 (3): 257-274.

– – -. 2018. “The Sound and Spectacle of Philippine Presidential Elections, 953-1998.” Musical Quarterly, 100/3-4 (Jul 2018), 297-339.

– – -. 2018. “The New Manila Sound: Music and Mass Culture, 1990s and Beyond”, PhD dissertation, University of Cambridge.

Gaerlan, Barbara S. 1999. “In the Court of the Sultan: Orientalism, Nationalism, and Modernity in Philippine and Filipino American Dance.” Journal of Asian American Studies2 (3): 251-287.

Gonzalves, Theodore S. 2007. Stage Presence: Conversations with Filipino-American Performing Artists.St. Helena, CA: Meritage Press.

– – – . 2010. The Day the Dancers Stayed: Performing in the Filipino/American Diaspora. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Jimenez, Earl Clarence. 2016. “The Life of a Drum: The Tboli T’nonggong. Studia Instrumentorum Musicae Popularis IV (New Series),1370148.

—. 2016. “Sounding the Spirit.” Sabangan2, 37-50.

—-. 2019. “The Divine Sound: Acoustemology of Faith in a Religious Community.” PhD ethnomusicology dissertation, Philippine Women’s University.

—. 2019. “The Entanglement of Space and Sound in Tboli Music Instruments.” Studia Instrumentorum Musicae Popularis VI (New Series),145-154.

—. 2020. “Memories of Sounds: An Archiving Project in Two Aural Communities.” Asian European Music Research Journal5(Summer), 1-8.

Labrador, Roderick N. 2002. “Performing Identity: The Public Presentation of Culture and Ethnicity among Filipinos in Hawai’i.” Journal for Cultural Research6 (3): 287-307.

Macazo, Crisancti L. 2019. “Music and Image the Soundtrack of Manuel Conde’s Extant Films, 1941-1958.” Phd in music dissertation, University of the Philippines.

Mangaoang, Aine. 2013. “Dancing to Distraction: Mediating ‘Docile Bodies’in Philippine Thriller Video.” Torture23 (2): 44-54.

– – -. 2015. “Performing the Post Colonial: Philippine Prison Spectacles After Web 2.0.” Post Colonial Text9 (4).

– – -. 2019. Dangerous Mediations: Pop Music in a Philippine Prison Video. New Approaches to Sound, Music, and Media. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Matherne, Neal. 2013. “Bayan Nila: Pilipino Culture Nights and Student Performance at Home in Southern California.”Asian Studies: Journal of Critical Perspective on Asia49 (1): 105-127.

Mendoza, Lara Katrina T. 2020. “Pag-aambag sa Eksena at Kultura (Making a Contribution to the Scene and Culture): The Meaning of Contemporary Hip-Hop Performance Among Youths in Manila, Philippines,” PhD in music dissertation, University of the Philippines.

Miranda, Isidora. 2020. “Dissonant Voices: Tagalog Zarzuela and the Politics of Representation in the Philippines, 1902 to 1942,” PhD dissertation, University of Wisconsin.

Montano, Lilymae. 2013. “Claming Social Justice in a Cordillera Community in the Philippines: The Ifugao Himong Revenge Dance.” In Proceedings of the 2nd Symposium of the ICTM Study Group on the Performing Arts of Southeast Asia, Manila, 2012, 130-133. Manila: Philippine Women’s University.

—. 2016. “From Village Ritual to Banaue Imbayah Festival: The Case of the Ifugao Himong Revenge Dance.” Sabangan2, 89-113.

Moon, Krystyn R. 2010. “The Quest for Music’s Origin at the St. Louis World’s Fair: Frances Densmore and the Racialization of Music.” American Music 28 (2): 191-210.

Muyco, Maria Christine M. 2017. Music of the ATA/ATI of Boracay in their Struggle for Land and Celebration of Life. University of the Philippines- Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Development. Audio CD.

– – -. 2018. “Salampati(Choral Arrangements of Bicol Folk Songs), editor. Manila, Phil.: National Commission for Culture and the Arts.

– – -. 2019. “Hearing Ginhawa In-and-Out and Across Cultures”. In Danyag. Philippine Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, issue no. 2, volume 22. OVCRE, UP Visayas

– – -. 2019. “Mumunting Tinig, New Works for Children’s Choral Pieces. (Entries: “I-angat ang Araw”; “Muklat”; Bigkas-Titik”; “Tumindig”; “Hakbang sa Dulo”; “Kapilas ng Buhay”; “Ako at ang Kalikasan”; “Pagbagkas-Bigkas”; “Kurubingbing Kurubawbaw”). The National Commission for Culture and the Arts. Audio CD.

– – -. 2019. “Ginggala: The Tai Yai’s Divine Gift Through Music and Dance” (with co-author: Khanithep Pitupumnak, Phd, Chiangmai University, Thailand). Perspectives in the Arts and Humanities in Asia, 1 (9).

National Commission for Culture and the Arts. Sagisag Kultura. Volume1, 2, 3. (Music/Dance), edited by Raul C Navarro. Manila: National Commission for Culture and the Arts.

Navarro, Raul C. 2001. “Ang Musika sa Pilipinas: Pagbuo ng Kolonyal na Polisi, 1898-1935” Humanities Diliman, 2 (1): 45-68.

– – -. 2004 “Musika sa Pampublikong Paaralan sa Pilipinas, 1901-1930” Daluyan: Journal ng Wikang Filipino, Vol. II. Quezon City: Sentro ng Wikang Filipino, UP Diliman. pp. 163-175.

– – -. 2008. “Ang Bagong Lipunan, 1972-1986: Isang Panimulang Pag-aaral sa Musika at Lipunan” Humanities Diliman,5 (1,2): 47-77.

– – -. 2016. Musika sa Kasaysayan ng Filipinas: Pana-panahong Diskurso. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

– – -. 2017. “Apat na Taong Pagsikat ng Nakapapasong Araw: Musika sa Filipinas sa Panahon ng Hapon, 1942-1945.” Plaridel: A Philippine Journal of Communication, Media, and Society, 14 (2): 1-24.

– – -. 2017. “Mula Mga International Exposition tungong ‘Manila Carnival’: Pagtatanghal ng Filipino bilang ‘Tribal People’ at ‘Beauty Queen’ sa mga Exposisyong Industriyal at Komersiyal” Humanities Diliman, vol. 14 (2): 64-90.

– – -. 2019 “Musika ng Pananakop: Panahon ng Hapon sa Filipinas, 1942-1945” Humanities Diliman16: 1-46.

Ng, Stephanie. 2005. “Performing the ‘Filipino’ at the Crossroads: Filipino Bands in Five-Star Hotels Throughout Asia.” Modern Drama 48 (2): 272-296.

Nono, Grace. 2014. “Babaylan Sing Back: Philippine Shamans on Voice, Gender, and Transnationalism,” PhD Dissertation. New York University.

Pisares, Elizabeth. 2008. “Do You MIs(recognize) Me: Filipina Americans in Popular Music and the Problem of Invisibility.” InPositively no Filipinos Allowed: Building Communities and Discourse, edited by Antonio T. Tiongson, Edgardo V. Gutierrez, and Ricardo V. Gutierrez, 172-198. Pasig City: Anvil Publishing.

Porticos, Peter John. 2017. “The Vision of Reynaldo Reyes: Erudition in Piano Performance and Pedagogue.” PhD ethnomusicology dissertation, Philippine Women’s University.

Prudente, Felicidad A. 2016 “Pinoy Jazz,” “Pinoy Pop,” “Pinoy Rap,” and “Pinoy Rock.” In Pop Culture in Asia and Oceania edited by J. Murray and K. Nadeau (pp. 35-39). California: ABC-CLIO, 2016.

—. 2011. “Asserting Cordillera Identity Among the Indigenous Peoples of Northern Philipppines.” In Proceedings of the 1stSymposium of the ICTM Study Group on Performings Arts ofSoutheast Asiaedited by M.A. Nor, P. Matusky, T. Sooi Beng, J. Kitingan & F. Prudente (pp. 25-30). Malaysia: Nusantara Performing Arts Research Centre and University of Malaya.

—. 2013. “Calling the Spirit: A Ritual of the Buaya Kalinga People of Northern Philipppines.” In Proceedings of the 2ndSymposium of the ICTM Study Group on Performings Arts of Southeast Asia edited by M.A. Nor, P. Matusky, T. Sooi Beng, J. Kitingan & F. Prudente (pp. 188-193). Manila: Philippine Women’s University, Philippines.

—. 2017. “Expressing Religiosity through the Performing Arts of the Tagalog-Speaking Peoples in the Philippines.” In Proceedings of the 4th Symposium of the ICTM Study Group on Performings Arts of Southeast Asiaedited by P. Matusky, W. Quintero, T. Sooi Beng, J. Kitingan & D. Quintero (pp. 25 – 30). Penang: Universiti Sains Malaysia.

—. 2019. “Expressing Grief for the Dead among the Buaya Kalinga of Northern Philippines.” In Proceedings of the 5th Symposium of the ICTM Study Group on Performings Arts of Southeast Asiaedited by P. Matusky, W. Quintero, D. Quintero, M. Hood, F. Prudente, L. Ross, C. Yong, & H. Hamza (pp. 106 – 108). Sabah: Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Environment.

—, ed. 1998.Antukin: Philippine Folk Songs and Lullabyes. Illustrated by Joanne de Leon. Manila: Tahanan Books for Young Readers.

—, 2019. Ed-Eddoy: An Ifugao Folk Song. Illustrated by Kora Dandan Albano. Manila: Tahanan Books for Young Readers.

–, ed. 2019. Kaisa-Isa Niyan: A Maguindanaon Folk song. Illustrated by Fran Alvarez. Manila: Tahanan Books for Young Readers.

—, ed. 2019. Pakitong-Kitong: A Cebuano Folk Song.Illustrated by Harry Monzon. Manila: Tahanan Books for Young Readers.

Sta. Maria-Villasquez, Gloria. 2016. ”The Nightingale Meets Nipper the Dog: Maria Evangelista Carpena and the Beginnings of Recorded Music Technology in the Philippines, ca. 1900-1915.” Sabangan2,64-77.

Schenker, Frederick J. 2016. “Empire of Syncopation: Music, Race, and Labor in Colonial Asia’s Jazz Age.” PhD dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Schenker, Frederick J. 2019. “Jazz and the British Empire: The Rise of the Asian Jazz Professional,” in Cross-Cultural Exchange and Colonial Imaginary, edited by H. Hazel Hahn, 263-279. Singapore: National University of Singapore Press.

Schoop, Monika.2019.“Independent Music and Digital Technology in the Philippines” Routledge Studies in Popular Music. New York: Routledge.

Talusan, Mary. 2004. “Music, Race, and Imperialism: The Philippine Constabulary Band at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair.” Philippine Studies Quarterly52(4): 499-526.

– – -. 2005. “Cultural Localization and Transnational Flows: Music in the Magindanaon Communities of the Philippines.” PhD dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles.

– – -. 2009. “Gendering the Philippine Brass Band: Women of the Ligaya Band and National University Band, 1920s-1930s.” Musika Jornal5: 33-56.

– – -. 2013. “Music, Race, and Imperialism: The Philippine Constabulary Band at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair.” In Mixed Blessing: The Impact of the American Colonial Experience on Politics and Society in the Philippines, edited by Hazel M. McFerson, 146-170. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group.

– – -. 2014. “Muslim Filipino Traditions in Filipino American Popular Music.” In Muslims and American Popular Culture, edited by Anne Rypstat Richards and Iraj Omidvar, 387-404. New York: Praeger.

Tan, Arwin Q. 2003. “The Academy of Music of Manila: A Legacy of Cosmopolitan Liberality.” CAS Review2 (4): 14-18.

– – -. 2007. “Evolving Filipino Music and Culture in the Life and Works of Don Lorenzo Ilustre of Ibaan, Batangas.” Master of Music thesis, University of the Philippines.

– – -. 2008. “A Review of Lawak Rondalya: Commemorative CD Album of Cuerdas nin Kagabsan,” Musika Jornal4: 216-218.

– – -. 2014. “Reproduction of Cultural and Social Capital in Nineteenth Century Spanish Regimental Bands of the Philippines.” Humanities Diliman11 (2): 61-89.

– – -. 2014. “Nasyonalismo at Pagkakakilanlan sa Musika ng Iglesia Filipina Independiente: Pagsusuri sa Misa Balintawak ni Bonifacio Abdon.” Saliksik E- Journal3 (2): 307-334.

– – -. 2014. “Approaching a postcolonial Filipino identity in the music of Lucrecia Kasilag.” Musika Jornal 10: 114-143.

– – -. 2016. “Finding the Filipino Spirit in Music.” Orden ng mga Pambansang Alagad ng Sining 2009,2014. Cultural Center of the Philippines and the National Commission for Culture and theArts, 139-155

– – -. 2017. “José M. Maceda at 100.” Perspectives in the Arts and Humanities Asia,7/2, 126-131.

– – -. Editor. 2018. Saysay Himig: A Sourcebook on Philippine Music History 1880-1941.Quezon City: The University Press

Tan, Joana Kristina S. 2020. “Shaping Filipino Pianists: On the Piano Pedagogy of Mauricia D. Borromeo.” Master of Music Education thesis, University of the Philippines. 2020

Taton, Jose Jr. 2017. “Performing the “Indigenous”: Music-Making in the Katagman Festival in Iloilo, Philippines.” In Proceedings of the 4th Symposium of the ICTM Study Group on the Performing Arts of Southeast Asia, Penang, 2016, 55-56.

Trimillos, Ricardo D. 2008. “Histories, Resistances, and Reconciliations in a Decolonizable Space: The Philippine Delegation to the 1998 Smithsonian Folklife Festival.” Journal of American Folklore 121 (479): 60-79.

UP College of Music. 2017. Saysay Himig: An Anthology of Transcultural Filipino Music (1880-1941), selected and annotated by Arwin Tan. Three-CD set.

Villegas, Mark R. 2016. “Currents of Militarization, Flows of Hip-Hop: Expanding the Geographies of Filipino American Culture.” Journal of Asian American Studies19 (1): 25-46.

Villegas, Mark R., Kuttin Kandi, Roderick N. Labrador, and Jeff Chang. 2014. ”Empire of Funk: Hip Hop and Representation. ”InFilipina/o America. United States of America: Cognella Academic Publishing.

Wang, Oliver. 2015. Legions of Boom: Filipino American Mobile DJ Crews of the San Francisco Bay Area.Durham: Duke University Press.

Wald, Gayle, and Theodore S. Gonzalves. 2019. “Island Girl in a Rock-and-Roll World: An Interview with June Millington by Theo Gonzalves and Gayle Wald.” Journal of Popular Music Studies31 (1): 15–28.

—

Selectively compiled by José S. Buenconsejo, PhD

with the assistance of Josephine Baradas, URA of UP College of Music